When the organization started is a moot point when you consider the impact it has had on mothers, fathers, and children across Georgia over the last 40-plus years.

When the organization started is a moot point when you consider the impact it has had on mothers, fathers, and children across Georgia over the last 40-plus years.

Everyone, including Arno, knows it started with parents from an advocacy perspective. “These parents were pretty fierce,” shares Arno, who remembers the founding parents at the Georgia State Capitol and advocating for their kids.

The average statistic for people with Down Syndrome is one in 600, and Atlanta is fast growing city with a vast metro area. In serving families and caretakers from McDonough to Rome to Griffin to Buford, DSAA’s services need to be impactful and meaningful.

“When DSAA started, it was really resource-based. Over the years, it has transformed into a programmatic organization that aims to meet the community’s needs,” says Arno.

Following the needs has allowed DSAA to serve families across the state intentionally.

“Our direct programming includes Mom nights, a Hispanic support group, and a group called the Black Family Connection that we just started two years ago and are so proud of,” explains Arno, who considers DSAA more of a “support” agency. “We really follow the needs of our community.”

The Asociación Hispana de Sindrome de Down en Atlanta, or the Hispanic Down Syndrome Association of Atlanta, is 25 years old and one of the oldest ones in the country.

“The challenges for the Hispanic community are a little bit different than some of the other challenges that you might see with an English-speaking community,” says Julianna Cebollero, a DSAA board member. Cebollero received a prenatal diagnosis of Down Syndrome for her son, now two-and-a-half years old and found DSAA before he was born.

Cebollero references challenges such as documentation, education and reading levels, technology, transportation, and communication.

“There are barriers like, ‘how do I even get my child enrolled in the school system?’,” shares Cebollero. “We’ve had families not know that special needs programs exist for their children. The other thing is a lack of knowledge of resources. There are a lot of transportation barriers as well.”

Additionally, barriers through medical services also can be daunting and cumbersome. Families must have a medical interpreter, but it can be difficult to navigate if you don’t speak the language. That is why DSAA’s Hispanic support group is so important.

“The hardest thing for the Hispanic families is language and finding interpreters. We used to have more educational programming and now we’re trying to shift our programming to more of the individual versus the larger group to see if we can help support families better in that way,” adds Arno.

While phone trees and group gatherings were the norm, the pandemic challenged DSAA to pivot from the way it reached the statewide Hispanic community. The organization focused on utilizing technology such as social media and Zoom calls to reach the population but found that the learning curve was even larger than imagined.

“We really tried to encourage the use of social media in a population that traditionally may not resort to social media as often. We identified that some families have trouble with logging into a Zoom call. This is all new to them,” she added.

People came together to help families in need. Parents worked together with other parents to help people navigate Zoom. DSAA even created a short video on opening up a Zoom call that is now available to all families.

DSAA’s website can also be completely translated into Spanish. The Hispanic family’s group also partners with other organizations that help connect with new parents. Being able to bring the families and connect them to DSAA from either prenatal or at diagnosis helps build relationships and provide access to early intervention programs.

“This keeps us connected as a community from the beginning and not let the children fall through the cracks and provide what’s best for them in their development,” says Cebollero.

To Arno, the impact needed to go further. Black families were missing at the table. She’d see families at the organization’s annual Buddy Walk but never saw them through their actual programs.

“I couldn’t figure it out,” said Arno. “I would go to them and say, ‘I don’t understand. You’re coming for Buddy Walk, but I don’t see you at any other time. It came down to not seeing people that looked like them. I didn’t have people on my board that looked like them. I didn’t have people at my programming that look like them. We discussed things like wills and trusts that those parents in that community are not thinking about. They’re thinking about getting support with bills or getting childcare. I was answering the wrong questions for them.”

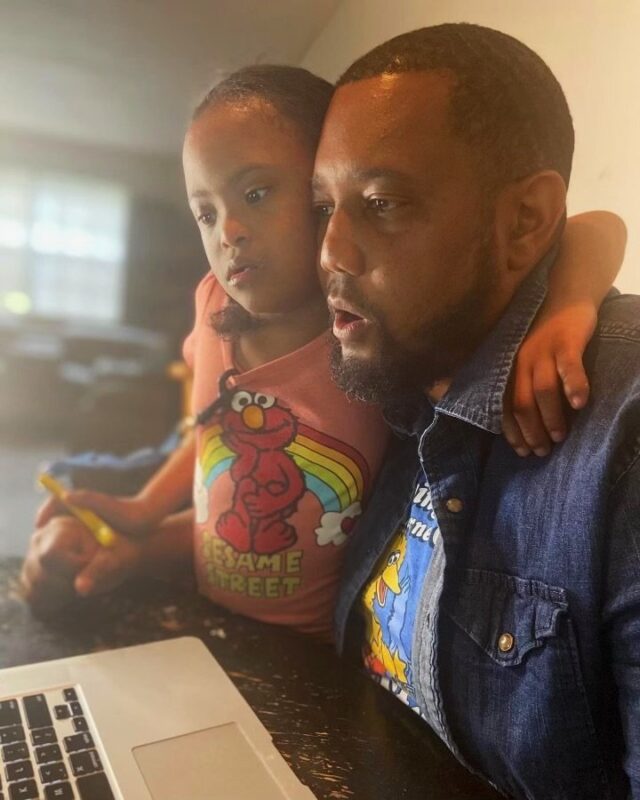

In 2021, DSAA founded the Black Down Syndrome Family Connection program. It was created from an expressed community need to gather Black families to connect, share resources and ask questions related to the Down Syndrome community.

“We were tapped to be taskforce initially to determine what the need was and give a perspective of what it’s like to be a parent of a child or be a person with Down Syndrome and be Black,” says Mya Prowell, chairperson of the DSAA Black Family Connection.

The group is intentionally focused on the issues surrounding the Black community. Prowell explains, “First and foremost, the thing is that the [Black community] doesn’t want to accept the disability. We find it hard to accept that there is anything different about our child. And so the thing is, is consistently trying to normalize them to what we’re used to. The second thing is miseducation or being uneducated, like not truly knowing the extent what Down Syndrome truly is. And then the third thing is the financial aspect.”

Black people account for a considerable amount of the poverty level, resulting in lack of access to certain things like time to get their children to therapies because they have other children.

“They have a difficult time navigating just day to day,” shares Prowell. “And then when it comes to government-assisted programs like Medicaid, they don’t have the service providers all the time. It’s a huge disparity regarding being knowledgeable about medical conditions.”

What started with four parents has grown from a task force to a committee of five. Its Facebook group has over 180 members. The group also hosts meetups statewide to ensure parents can meet, mingle, and share information.

Advocacy was the foothold of how DSAA started back in the 1970s. Prowell agrees that families must be at the Capitol but is realistic in meeting the parents where they are.

“Our families don’t even know what advocacy means in the Down Syndrome community,” add Prowell. “We need to get our families to show up to IEP meetings. It starts there. It starts with medical appointments, making sure you speak up when you feel something is wrong. So just advocating at the lowest level is where we’re trying to get our families first.”

The support group is layered with issues that matter for the Black community.

“This world is already hard to navigate as a Black person, and then as a Black male too,” says Prowell, thinking of her 11-year-old son Tristan. “And there is a very high rate of males with special needs in prison because nobody realized they really had one. The great thing about Tristan is that you can see the disability on his face. But we have to factor in that people are not going to care [about] not putting him in jail because he was at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

So, that’s why Prowell encourages Black families with children who have Down Syndrome to get involved at the very basic level. “We need to show up. Our first steps are getting our families and parents to help themselves first,” she adds.

And, while the focus has been on babies and new moms, DSAA partnered with Gigi’s Playhouse Atlanta, the local chapter of a national organization that serves the Down Syndrome community, to support its young adults through Gigi’s adult transition program called EPIC.

Howie Rosenberg, executive director of Gigi’s Playhouse Atlanta, is proud of the partnership with DSAA and collaborating resources to help families thrive.

With its EPIC program, “We mix life skills, independence, fun, friendship building, and advocacy teamwork. Our curriculum considers, ‘what do young adults need to do?’ They need to learn how to cook, they need to learn how to do their laundry, they need to learn how to live independently,” says Rosenberg. Leaders in the community like Arno or Rita Young host trainings through EPIC for young adults to build independence and confidence.

The partnership with DSAA and Gigi’s Playhouse Atlanta has allowed both organizations to increase their impact and reach for the community they serve. Gigi’s serves about 1,100 families in Atlanta.

Reflecting on her career at DSAA as executive director, Arno says, “It’s actually one of my proudest things that I’ve done in my career in terms of building this community. We fight for inclusion every day. It’s easy for me to say we need to be inclusive and all that, but it’s just not. And it’s not going to be unless I intentionally do something.”

Visit their website to learn more about the Down Syndrome Association of Atlanta.