“Believe me,” said Javier Cremer, a second-year student at Georgia Tech University’s Excel program, “if I hadn’t become an advocate with a disability, I couldn’t find my true self right now.”

Cremer is amongst the few that are a part of the upcoming generation of disability advocates, following on the backs of giants like Justin Dart, Judy Heumann, and Georgia’s own Lois Curtis. Among many other advocates, Dart and Heumann led the fight for landmark legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

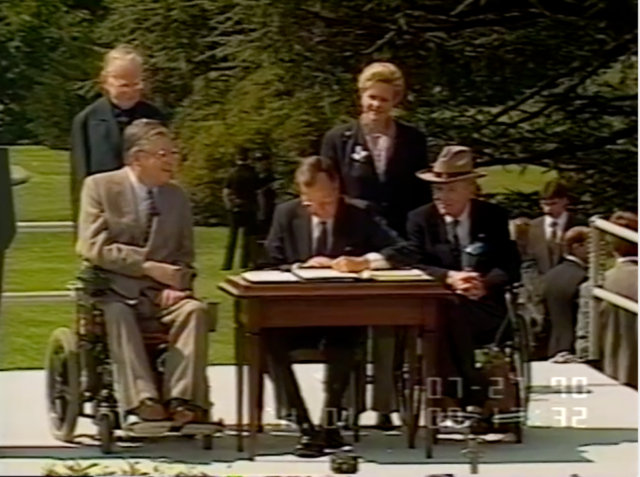

It has been over 30 years since the passage of the ADA, which became an all-encompassing civil rights legislation for people with disabilities across the country. It created momentum for other laws and rulings, such as Olmstead. Lois Curtis was the plaintiff in the Supreme Court’s L.C. versus Olmstead, which transformed the way states provide services to be more community-based rather than institutional settings.

And these giants, amongst many, have left their indelible mark on disability history. Lois Curtis passed away in November 2022 at her home in Clarkston, Ga. Judy Heumann passed away in early March 2023 at the age of 75, causing ripples of dedication, memories, and moments posted across social media about her impact on disability rights.

This leaves a looming question among today’s advocates: “Who’s next?”

Groundhog Day

“People like me, when we go to the Capitol some days, and I run into all my colleagues, we sort of call it Groundhog Day,” says Sheryl Arno, Executive Director of the Down Syndrome Alliance of Atlanta, referring to the 1993 movie where the main character relived the same day over and over again.

“We see the same people, same advocates at the Capitol. And we know that we need that next group coming up. It’s really scary because it’s hard to find advocates, especially advocates that don’t have children with disabilities. After all, we need both. It’s so important because otherwise, we will be in trouble.”

People who have been in the advocacy world for a long time are excited for a new batch of young people to join the conversation and feel that their voices have been missing for too long.

“We run the risk of all the hard work that’s been happening in the last 50 years becoming stagnant,” said Molly Tucker, Training and Advocacy Manager at Georgia State University’s Center for Leadership in Disability (CLD). “That’s the conversation Mark [Crenshaw] and I had all the time. It was always, ‘we’ve got to get more people in the rooms.’ When I started at CLD, he made the joke that he could tell you, every meeting he would go to, the 10 people that would be there. And he’s like, ‘I’m tired of the same 10 people being everywhere.’”

But, this generation is finding their own space to make their impact for what matters to them.

Paving the Path Through History

To know where you want to go, you must know where you have been.

A program that has been gaining momentum is Project SETA, or Students Enhancing Their Advocacy, through Georgia State University’s CLD. The project is funded by the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD).

A program that has been gaining momentum is Project SETA, or Students Enhancing Their Advocacy, through Georgia State University’s CLD. The project is funded by the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD).

An issue that is especially important to the Project SETA team is learning about past leaders and how existing legislation works in the modern world.

“We talk about the 504 sit-ins and the signing of the ADA,” said Tucker, who also leads young students through Project SETA. “They’re in college and were born post-ADA. It is important for them to know how we got to where we are and how we can continue moving forward.”

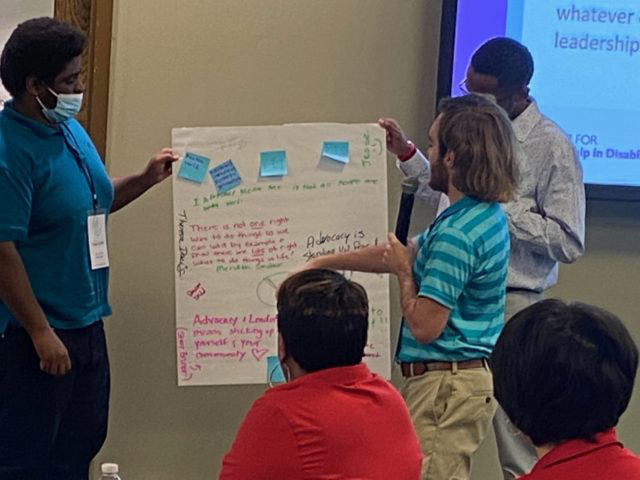

These lessons have helped Project SETA students hone their focus on the most important issues.

Regarding Georgia’s youth advocates, Mark Crenshaw, Assistant Director at the CLD, mentions the effectiveness of young people being masters in their own experiences and topics of choice.

“What excites me,” says Crenshaw, “is that they are clear about what they’re most passionate about. They are not trying to advocate for 15 things.”

What They Care About

Noelle Ford, who is about to graduate from Kennesaw State University’s (KSU) Academy for Inclusive Learning and Social Growth program, started her advocacy journey at her college.

On campus, specific pedestrian bridges had about a one to one-and-a-half-inch gap. “And I would get stuck,” said Ford, who uses a wheelchair. “People are walking; we also have skateboarders, people using scooters, and things like that. Some people actually tripped, and I thought, ‘I can actually get them to flatten this because if you think about it, people can also flip and injure themselves.’” She advocated with the university and made pedestrian bridges accessible for all.

Her advocacy didn’t stop there. She also worked with the university to put “Push” buttons, or sensory doors, in some of the bathrooms in one of the campus’ main buildings.

However, Ford is also noticing flaws in ADA’s call for accessibility.

“Accessibility is just more of an umbrella term,” adds Ford. “I wish the ADA and accessibility were way more specific. Like, one bathroom could have this, one bathroom could have that; I wish it would be pinpoint accurate. Say all bathrooms need automatic doors, all bathrooms need grab bars…pinpoint.”

Myles Henderson, 22, is a new self-advocate and is realizing the impact and importance of his voice. During the legislative session this year, he went to the Georgia State Capitol for the first time to advocate for waivers, increasing the rate of Direct Support Professionals and employment.

Seeing it for the first time, he was awestruck by the Gold Dome. “It was amazing,” recalls Henderson. “I liked the experience and the opportunity to tell my story.” Henderson testified for both the House Budget and Senate Appropriations Committee on the importance of the waivers and increasing the rate for Direct Support Professionals. He is currently on the waitlist for a NOW/COMP waiver.

Henderson also advocated at GCDD’s Employment Advocacy Day. “I love to work,” said Henderson. “And we want to work and we want more opportunity.” Henderson used to work at Kroger and Uncle Maddio’s Pizza. Now, he volunteers at the Boys & Girls Club as a greeter and works with the children who are a part of the organization.

Modern Day Advocacy

Additionally, with the ever-changing media landscape and technology, accessibility and the ADA are coming into play. While the law only counted for physical buildings and structures such as curb cuts, how people with disabilities and without disabilities communicate today has caused a conversation on the extension of the ADA through communication portals.

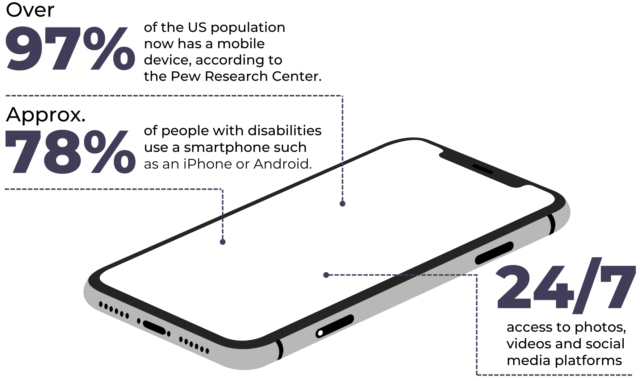

Over 97% of the US population now has a mobile device, according to the Pew Research Center. And approximately 78% of people with disabilities use smartphones like iPhones or Android. This means there is access to photos, videos, and social media platforms 24/7.

Over 97% of the US population now has a mobile device, according to the Pew Research Center. And approximately 78% of people with disabilities use smartphones like iPhones or Android. This means there is access to photos, videos, and social media platforms 24/7.

When the world shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many people with disabilities were isolated as in-person programs and events were canceled. Many being immunocompromised, their health and safety also required them to stay at home, including till today. They turned to social media to stay connected with each other and have a sense of community.

Social media platforms became even more important than ever for this generation of advocates by creating a community and a space to share.

“We use social media. That’s our platform,” said Stripling, who wants to use social media to bring more awareness about the deaf community. “Watch us sign, act, and get involved in the music world. It’s an identity thing. We want to be recognized. When people see it, they recognize us, and that’s how we get the ball rolling and keep the momentum. And then that pushes the door more and more and more open.”

“I see deaf people using social media all the time, and that’s how we can disseminate the information, videos, encouragement, and fostering people’s growth,” she continues.

Social media is more present in today’s younger generation than ever. Platforms like TikTok, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook have carried the message faster for the disability community.

They are using these spaces to educate about disability history, disability issues, and also about everyday life.

According to an article in Refinery29, TikTok allowed disability advocates to bring attention to the Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act, ensuring that people with disabilities don’t lose their SSI benefits if they choose to get married or work part-time.

Recent corporate changes at Twitter has concerned the #DisabledTwitter and #DisabilityTwitter community. The short-form social media platform allowed individuals with disabilities to come together to educate, communicate, socialize, and advocate for issues that matter to them. Some even considered it a lifeline, according to an article in The Washington Post.

With security issues and now the disbanding of the accessibility team, the access that Twitter provides has advocates wondering about the future of the space and its impact for the community.

Why are these spaces important? The #DisabilityTwitter hashtag reached over 1.2 million people in seven days when used in tweets and posts, according to BrandMention.

On TikTok, July’s Disability Pride Month hashtag #DisabilityPride surpassed 300 million views, meaning that the message and advocacy efforts resonate with the disability community and community-at-large.

The Making of Future Leaders

Future leaders come from today’s advocates. The key is to develop more peer leaders so young advocates can build a path that meets their moment while they learn from those who have paved the way.

When asked about her next steps in advocacy, Stripling gets excited about the thoughts of coming to Atlanta and going to the Georgia State Capitol. And she realizes that there is a lot of work to do.

“Our next and new challenges are different, and we have some catching up to do,” laughs Stripling. “ That’s okay. We’re doing it. We’re catching up and we’re fighting for our people, our community by mentoring and leading. That’s how we can actually form future leaders.”

Darien Todd, a self-advocate and Georgia State University’s (GSU) Community Advocate Specialist can’t believe that he’s now a trainer for advocacy.

“If you would have asked me when I was in high school if I pictured myself mentoring young advocates and talking to them about very important topics… I would have looked at you and said, ‘no, I don’t think that’s the position I would be in.’ But I am in this position, and I love every moment of it,” says Todd, who trains young advocates through Project SETA and is a graduate of KSU’s Inclusive Post Secondary Education (IPSE) program.

Local, statewide, and national programs are noticing the need to train young disability advocates. Besides programs like Project SETA, other local programs also offer peer-to-peer interaction and training for advocacy and leadership.

Howie Rosenberg, executive director of Gigi’s Playhouse Atlanta, speaks of the organization’s EPIC (Empowerment Participation Independence Community) program built for young adults. Amongst many offerings of the program that teaches independent living, employment skills, and socialization, one of the key focuses is advocacy.

“We try to instill to them that their voice matters,” explains Rosenberg. “We start with things like the President of the United States, the Governor of Georgia – every single person is elected by voting. We ask them, ‘do you know how much your vote counts? You get one vote.’”

For Rosenberg, it’s a way to teach young advocates that they are all equal in the decisions people make on who represents us. “It really is one of the few places where we are all equal,” says Rosenberg. “We all have that one vote. And so we talk about, like, how to decide on who we want to represent us. Do we want somebody to represent us that doesn’t care about people with disabilities?”

Thinking of the impact of the next generation, Rosenberg recalled the advocacy work around Gracie’s Law, where families and young advocates came together to encourage Georgia lawmakers to pass a law that allows people with disabilities to receive equal consideration for organ transplants.

At that time, the advocacy efforts resulted in Gracie’s Law being passed to zero in the State of Georgia 165. “It passed because the advocates made it pass. So they understand that they were part of it, and if they were not out there fighting for themselves and others, it wouldn’t have happened.” Governor Brian Kemp signed Gracie’s Law making it law in 2021.

Programs like Gigi’s EPIC and Project SETA are just a few that are shaping the next generation of advocates nationwide. Partners in Policymaking, a national advocacy training program that the Minnesota Council started on Developmental Disabilities, had programs such as Junior Partners and Youth Leadership that were activated by Delaware and Oklahoma, respectively. The National Consortium on Leadership and Disability for Youth uses learning, connecting, thriving, working, and leading to guide its work for youth leadership.

Sharing knowledge expresses hope and compassion for current and future generations. The disability giants have shown the world that better lives are possible among the disability community and can be achieved through activism, innovation, and heart.

“I’m incredibly hopeful,” reflects Crenshaw. “I get to spend time in spaces with young people who are motivated and learning the skills needed. It doesn’t take much time in a room with folks in their teens and twenties and thirties to get really excited about this movement’s next generation of leaders.”