“The world will be missing out if we don’t do what is necessary. And we clearly have shown that what is necessary are these Direct Support Professionals,” remarked Pam Walley, executive director of Georgia Options. “We’re going to miss out on the contributions of a lot of really talented, wonderful, giving, creative, amazing people,” she added.

Walley’s work at Georgia Options helps support people with disabilities in their homes and in the community. But, just like other disability support organizations across Georgia and the nation, it is struggling to recruit and retain Direct Support Professionals (DSPs).

The DSP workforce shortage has been an on-going issue for decades, but it has now become a crisis. People who rely on DSPs for care and community connection are left with few caregiving options. Between poverty-level wages, insufficient benefits, inadequate training, and a lack of advancement opportunities, recruiting and retaining DSPs is a growing challenge.

A DSP is defined as an employee who spends at least 50% of their time providing direct support for a person with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD). Marquise Little, former staffing coordinator at Georgia Options, spoke about some of his difficulties recruiting DSPs over the last few years. He reported that people would frequently use “easy apply” without fully reading the job description or pay rate. Additionally, applicants wouldn’t show up for interviews. Little explained, “You might have 10 interviews lined up and you have one [show up].”

DSP Wage Inequality

A study by the Institute on Community Integration at the University of Minnesota and the National Alliance for Direct Support Professionals, found that the average hourly DSP wage was $13.92 in 2020, with ranges between $6.25 and $40 per hour. In Georgia, wages have been found to be between $10 and $11 per hour, far below Georgia’s living wage of $20.80 for an individual.

One reason for low pay is that the profession does not have a Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). SOCs are an important tool for the different levels of government to identify employment trends and create policies, including rate-setting for state Medicaid programs. This has left policymakers without data that enables them to make informed decisions to help with recruiting, retaining and paying DSPs a fair wage.

Impact from the Pandemic

The pandemic has made the crisis worse by causing big businesses to significantly increase entry-level wages to attract more employees during a global shortage. As disability organizations rely on limited Medicaid funding, they are left without a way to compete with many retail and restaurant businesses like Target or McDonald’s.

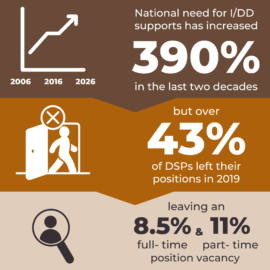

Georgians with disabilities and their families are suffering. And, many are being forced to make difficult decisions about their short and long-term care. The national need for intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) supports has increased by 390% in the last two decades.

Georgians with disabilities and their families are suffering. And, many are being forced to make difficult decisions about their short and long-term care. The national need for intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) supports has increased by 390% in the last two decades.

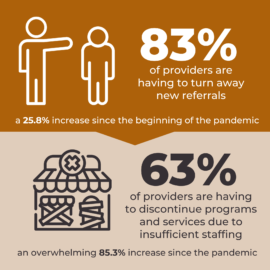

A 2022 report by ANCOR stated that 83% of providers are having to turn away new referrals, a 25.8% increase since the beginning of the pandemic. And, 63% of providers are having to discontinue programs and services due to insufficient staffing, an overwhelming 85.3% increase since the pandemic.

Not only do these challenges impact the safety and standard of living for people with disabilities, but also they interfere with their legal right to participate in the community and have the same opportunities as people without disabilities, as outlined by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Direct Support Professionals commonly support people with disabilities in their daily activities, which can include anything from changing clothes to toileting to running errands to advocating to employment support.

But, people on the ground floor, like Little, see the complexity and nuance reflected in the position. He refers to DSPs as the “pieces of the car that you don’t necessarily see operating,” but are, in fact, “the backbone of the developmental disabilities population.”

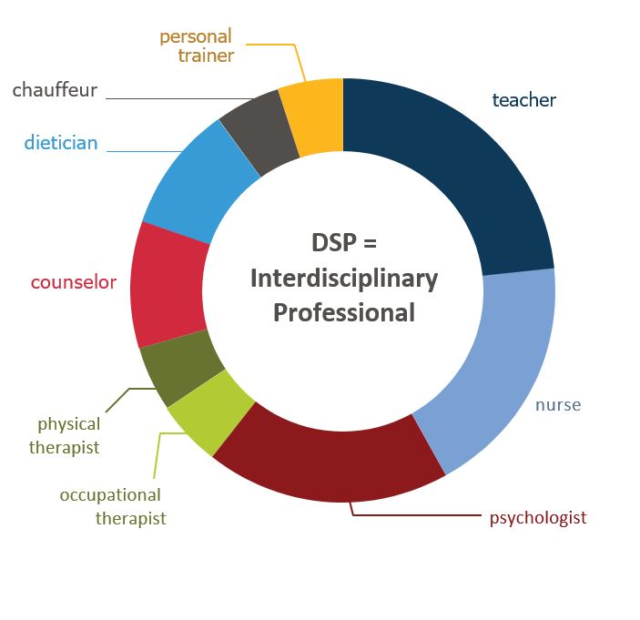

In a 2017 President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities (PCPID) report, the committee presented data depicting the various and numerous roles that DSPs hold, and the average amount of time spent performing those roles (Figure 1).

The report further stated, “Like teachers, [DSPs] develop and implement effective strategies to teach people new skills. Like nurses, they dispense medications, administer treatments, document care and communicate with medical professionals. Like various allied health professionals, they assess needs, implement specific treatment plans and document progress. Like social workers, they get people connected to community resources and benefits. Like counselors, they listen, reflect and offer suggestions. DSPs provide whatever support it takes so people can live and participate in their communities with greater independence and dignity” (pp. 15-16 of the report).

DSP from Georgia Relates to the Issues

Thom Strickland, a DSP at Georgia Options, can relate. He, too, has had to take on many different roles during his career as a DSP. Strickland has been a DSP for 19 years and has been caring for the same individual, Jason. Jason is nonverbal and Strickland reports that he is lovably stubborn. Strickland ensures that Jason has ample time within the greater community, and he frequently provides transportation and community navigation.

Strickland notes that Jason doesn’t need to go to the grocery store three times a week, but getting out and interacting with the world is beneficial to everyone. And, after years of getting to know Jason, Strickland serves as interpreter and translator by relaying the “minutia of [Jason’s] needs and his subtle way of communicating” to others.

“I’m not going to say he has a hard time communicating his needs if you know him, but if you were just to come in, like say I’ve taken him to doctor’s appointments, that sort of thing, often they don’t know what to do with him. They don’t know how to communicate with him,” Strickland explained.

Though his role as a DSP was supposed to be a temporary way to fill some extra hours over the holidays, Strickland fell in love with Jason and now considers him family.

“I kept saying, I’m going to do it three more months, I’m going to do it two more months. And here we are 19 years later and I’m still with the guy,” he remarked.

Though Strickland has been a DSP for nearly two decades, it has never been a position that could financially sustain him. He has worked additional jobs to support himself. Between managing a kayak store to playing music, Strickland regularly clocks 100 hours per week. When asked how he does it, his response was, “lots of coffee.”

DSPs like Strickland are few and far between due to the unsustainable lifestyle, but it is fair to say that DSPs who stay in the job are the caregivers of our society.

At Georgia Options, Little started off as a DSP and worked his way up to operations manager. Like Strickland, Little supplemented his DSP income with side jobs, including Uber and DoorDash. He even took a pay cut from his previous restaurant job.

But his roots remain grounded. “I actually realized that I enjoy what I do, I felt like I was making a difference,” he said. “I am forever a DSP.”

To learn more about the DSP Workforce, visit https://nadsp.org/

A Path to Direct Support Professional Retention

Entities across the country are putting their heads together to come up with solutions to the Direct Support Professional (DSP) crisis. Putting aside the need for increased Medicaid funding, people like Carol Britton Laws, clinical professor of disability studies, principal investigator and training director at the University of Georgia are helping to provide multi-layered approaches to DSP retention.

One of those approaches has been the development of a DSP employee resource network. Borrowing concepts from Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), the network would connect DSPs with resources when personal circumstances might prevent them from getting to work.

Organizations, both big and small, could buy into the DSP EAP concept and get a success coach who would work directly with staff to identify and utilize existing community resources. The success coach would help answer questions like:

“What do I do if my car breaks down and I don’t have the money to get it fixed? How can I access food banks in my area with the price of food and inflation being higher than my wages? How can I find childcare if my child’s school is closed or my child is sick? How can I pay for the internet in my home in order to access professional development training?”

With the support of Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD) funding, Service Providers Association for Developmental Disabilities, Georgia’s State Provider Association on Developmental Disabilities, and the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities will launch a pilot program in 2024.

“I think that [it] will go a long way in helping committed staff who really want to show up, [but] are struggling in their own lives, to really be present for people who are receiving supports through their organization [and] be able to stay on the job,” stated Britton Laws.

Additionally, Britton Laws has been part of creating a DSP credentialing trajectory, which would allow both new and seasoned DSPs to exhibit mastery in specific skills to gain professional recognition. And, with such high turnover in the field, she and other stakeholders believe that developing a career path with recognition and pay raises will help retain staff for longer than the current 6-month to one-year average. Britton Laws spoke about the present and past expectations of DSPs, noting that it is “typically considered to be a career where people aren’t expected to have a high level of education to enter it.” But there are skills, knowledge and values that are required for a DSP to be successful that go beyond the standard medication administration and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training.

Britton Laws explained, “What staff really need is to have a set of competencies that helps them to navigate how to support an individual in a space where they might be trying to reach goals that are related to their own health or employment or relationships or being involved in their community.”

These tactics are positive steps towards the system overhaul that will be required to provide dedicated DSPs with the quality professional experiences that they deserve.