When Georgia legislator Sharon Cooper, R-Marietta, heard from a constituent that there were residents making as little as 22 cents an hour, she had to do a double take.

“It seems like that is something out of the 1800s when we didn’t have child labor laws and they had children working for six cents an hour. It’s just antiquated,” she said.

Cooper gathered her team to research the issue and discovered that low wages for people with disabilities isn’t just a common practice, it’s part of federal law.

As a provision of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, he issued an executive order on Feb. 17, 1934, that permitted payment of individuals with disabilities below the minimum wage. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) that created a special exemption in Section 14(c) of the Act authorizing employers to pay wages much lower than the minimum wage to workers with disabilities. According to research by Advancing Employment, an advocate for inclusive employment in Georgia, these wage provisions were originally created to encourage the employment of veterans with disabilities in a manufacturing-centered economy.

In preparing to present a bill next year, Cooper’s team is studying efforts made nationally and in other states to phase out the federal law.

History of Subminimum Wages for People with Disabilities

From the FLSA came the term “sheltered workshop” which refers to an organization or environment that employs people with disabilities separately from others, usually with exemptions from labor standards, including but not limited to the absence of minimum wage requirements.

According to an article by Dr. Patricia Farrell in the Feb. 25, 2023, edition of BeingWell, sheltered workshops yielded benefits of developing and maintaining social and economic potential and providing differently-abled participants dignity and self-respect. Moreover, the skills empowered them to live independent lives.

However, the lack of regulatory standards allowed contracts between businesses and workshops that didn’t provide that workers would be paid anything near the minimum wage. In some states, such as Utah, this information is not available to the public, and workers may receive 50 cents an hour or less, Farrell wrote.

According to Farrell’s research, the average pay for people who work in sheltered workshops for people with disabilities varied greatly. While some workers are paid as little as $0.50 per hour, others receive between $3.34 and $5.49 per hour.

Additionally, an article produced in November 2022 for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Kansas City Beacon reported on sheltered workshops in Missouri. More than 5,000 adults with disabilities work in Missouri’s sheltered workshops, some earning less than $1 per hour, the report showed.

Instead of outrage, the individuals and their families seemed to strongly support sheltered workshops, the reporter said.

“They didn’t focus on the low pay or the dearth of other opportunities. Most said they were simply grateful for the jobs that the facilities offered,” wrote Madison Hopkins.

She concluded that the seemingly widespread support among sheltered workshop employees and their families masked the failure of the state to provide them with meaningful employment options.

Regardless of the intent, paying subminimum wages for the same work is discriminatory, said Cooper. She’s planning to introduce a bill in the 2024 Georgia General Assembly legislative session to phase out Section 14(c) of the FLSA.

“When you start to change laws like this, you have to be very careful that you don’t interfere with any other benefits,” said Cooper. “The other thing is that you can’t just go from 22 cents an hour to requiring a minimum wage for everyone. It would be nice to be able to do that when people work. But people just don’t like for laws to change that quickly.”

Having a law in the books is the direction that many advocates for people with disabilities want to go. In the meantime, there are other actions being taken to bring about parity.

Efforts to Provide Inclusive Employment for People with Developmental Disabilities

Since the FLSA was enacted, there have been other government actions set in place to get residents with disabilities into the workforce.

On May 8, 2018, Georgia’s Employment First Act (HB 831), which promotes employment as the first and preferred option offered to people with disabilities receiving government funded services, was signed into law. The state joined a national movement that included 45 other states with some form of Employment First initiative, legislation or executive order.

The year after the law took effect, the number of employed Georgians with intellectual or other developmental disabilities (I/DD) grew. According to the Department of Labor’s American Community Survey, there were 74,821 in 2018 and 82,876 in 2019 – the most recent data available. Similarly, the number of Georgians with I/DD who were employed and receiving Supplemental Security Income rose during the same time frame. According to data from the Social Security Administration, that number went from 7,854 in 2018 to 8,184 in 2019.

Additionally, a report commissioned by the Administration for Community Living (ACL) and Administration on Disabilities (AoD) and published by the National Disability Rights Network shows that reforms are growing.

- As of 2001, state vocational rehabilitation (VR) programs cannot count placements in segregated work as an employment outcome under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which authorizes public funding for employment services for individuals with disabilities.

- In 2014, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) amended the Rehabilitation Act to “maximize opportunities for individuals with disabilities, including individuals with the most significant disabilities, for CIE.”

- The WIOA amendments included a host of requirements around career counseling, informed choice and, among others, promoting self-advocacy and self-determination.

‘I’ve got to make it on my own’

There are many companies who’ve enacted their own diversity and inclusion policies where adults with I/DD work among the rank and file. They receive the same wages and benefits as others in the same or similar positions. Bruce T. Arnold, an associate in the garden department at Home Depot is one example.

“I work in a lawnmower section, the equipment section anywhere, like in the outside area,” he said during an interview for the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities.

The Home Depot gig is Arnold’s third job. He had worked in a sheltered workshop but needed to make a living wage to provide for himself and his family. The sheltered workshop company, Woodright Industries, offered job coaching and helped Arnold find work in the sanitation department with the city of Kennesaw. When that position was privatized, he ended up at Home Depot.

Arnold said a strong work ethic was instilled in him early on and he likes his job. When asked what he likes about it, his answer was simple, “It’s just dealing with the public. Helping people out,” he said. “But I do not let my disability affect what I do.”

He’s an advocate for giving people with disabilities the opportunity to provide for themselves by earning a living wage.

“I’m a type of person that I’ve got to make it on my own,” Arnold said. “I have been a willing, driven person that wants to get things done and not let things happen.”

Unfortunately, not every sheltered workshop turns into a regular wage situation.

Unfortunately, not every sheltered workshop turns into a regular wage situation.

“I know that we have one sheltered workshop still in Cartersville. And the thing is, the people were still making money off of the individuals coming in there and working for subminimum wage. And so it was like a business thing, which a lot of them are, it’s just business,” said Suzanne Clark, a supported employment specialist with Woodright Industries. “They treat [the workers] like they’re so ignorant that they won’t recognize those pennies.”

Clark encourages her clients to seek out training and job opportunities to help them maintain independence.

“We need to reach out to those individuals and let them know, ‘Hey, you can do this or that [and] you can make more money.’ And try to make them understand why that’s a good thing,” said Clark. “They need to be made aware of how worthy they are.”

Job Training, Placement Isn’t Charity

Preparing people with disabilities for job development and job training is what Briggs and Associates has done for about 35 years.

“It’s a community-based agency and so we actually don’t have an office. We’ve operated outside of an office since way before COVID,” said Emily Myers, region director for Briggs & Associates. “We’re really one of the earliest agencies to do what we do in Georgia, and continue to be one of the largest and in terms of outcomes, to have the more positive outcomes in terms of agencies internationally.”

Myers said the organization uses innovative ways to work with businesses.

“We’re out in the community all the time. We meet people where they live. We meet people in their preferred neighborhoods. … We spend a lot of time getting to know the individuals we serve. And so by doing that we have such a good sense of who they are, and what they are really good at. We really focus on strengths and kind of put the disability to the side for a minute,” she said.

She added that Briggs & Associates doesn’t limit itself to any particular industry.

“We go in and we look for a way to help them with their bottom line. … We don’t go in and just ask for a job, tell the story of what we do and expect that to be a fit – it’s not a charity in any way.”

The company employs what it calls a five-step strategy to get people with disabilities into the workforce earning fair wages:

- Identify the person’s skills, interests and conditions for success.

- Analyze sites/jobs to address accommodations and liability concerns.

- Design the training program.

- Consult with the business team to enhance understanding and interaction with the new employee.

- Provide ongoing support that may be needed to ensure success for continued employment.

“What we do is really look at what are some parts of a business’s operations that could be done more efficiently, effectively, maybe with a little more morale and excitement and look at what the business has just not been able to address within their current workforce,” said Myers. “And then we look within our client base to see if we have the right fit to be able to solve that business need. So it is a negotiation the whole way.”

Briggs & Associates has gained international recognition for being employment first focused and opposed to any sort of subminimum wage employment, as well as any non-competitive employment.

“Our job is to find the right fit. And that’s the challenge. So we do individual support. We do not serve people in groups. We don’t serve people in facilities. Everything’s community-based and everything is with a traditional employer at the going rate,” said Myers. “So no person we serve makes less than minimum. Our average is … about $12 or $13 an hour.”

And because the fight for fair wages is being waged in legislative chambers, Briggs & Associates does a lot of advocacy work by getting involved with groups that speak with representatives at the Gold Dome.

“[We want] to be sure that they understand that Employment First is the way to go for people in Georgia, and that subminimum wage should be eliminated completely.”

Success Begins with Policy Change

University of Georgia (UGA) professor Doug CrandelI agrees that there are several ways to end subminimum wages for people with developmental disabilities. He serves as public service faculty at the Institute on Human Development and Disability at the UGA and has worked for decades on ending the sheltered workshops and provider programs that rob workers of fair wages.

“I’ve got a sister with disabilities. I’m an advocate and I’ve worked in the field for 30 years,” he said. Crandell also authored Twenty-Two Cents an Hour: Disability Rights and the Fight to End Subminimum Wages.

Crandell says the companies making money off these individuals have strong lobbyists and win contracts to supply workers at subminimum wages.

“It’s just abuse after abuse after abuse,” he said, adding that the resistance is great to maintain the status quo.

And although Rep. Cooper is planning to introduce legislation next session to phase out the practice, there’s federal efforts to bring about the same outcomes.

“The Feds last year around this time, announced 14 states to receive from the Rehabilitation Services Administration grant funding, Georgia was one of them,” he said. “So we have examples of progress.”

Currently, 13 states are trying to ban or phase out subminimum wages, said Crandell. He pointed out that California has about 9,000 people on subminimum wages while Georgia has more like 200-250 people.

Currently, 13 states are trying to ban or phase out subminimum wages, said Crandell. He pointed out that California has about 9,000 people on subminimum wages while Georgia has more like 200-250 people.

“The bigger issue, though, is where do those folks go?” said Crandell. “And what we can see from the data is what we call provider agencies or entities that are supposed to be providing services for folks are just moving people into day programs instead of competitive integrated employment.”

His decades of research and advocacy, brought out an impassioned plea for reform.

“As it stands right now, in the United States, it is permissible to pay people with disabilities subminimum wages in 38 states. And we don’t know what will happen with the national bill. Because it’s stalled a little and … the lobbying continues,” he said. “So I’m so glad to talk to Representative Cooper and this is probably the best traction we’ve gotten, but … it’s important for anyone to understand, it really is just the first step. Because it’s not really the number of people who are on subminimum wages in Georgia, it’s the number of people who are also in day programs, who are not getting a chance to go out and work in the community. There are thousands of those people.”

Although there have been countless advocates, there is still a lot of work to do, he said.

Crandell has ideas of how to eliminate the unfair labor practices.

- Take advantage of Georgia’s robust economy by offering tax incentives to employers who offer fair wages to adults with developmental disabilities.

- Utilize the supports already in place such as the Employment First Council. Find ways to provide transportation and training to individuals who will benefit from those programs.

- Overturn the laws that allow the subminimum wage.

Once those provisions are put into place, the road to success should be smoother.

“I don’t see resistance on the business employer side,” said Crandell. “The biggest barrier to making these changes, whether it’s phasing out Georgia

subminimum wages or making sure folks with disabilities who are in day programs get an opportunity to work, it’s really our policies. It’s really provider agencies. I mean, there are community service boards, other providers who they’ll tell you, they don’t get enough funding, I don’t believe that.”

Crandell added, “And I also believe that businesses and industry are begging for people to come to work,” he said. “So all these things can be very creative.”

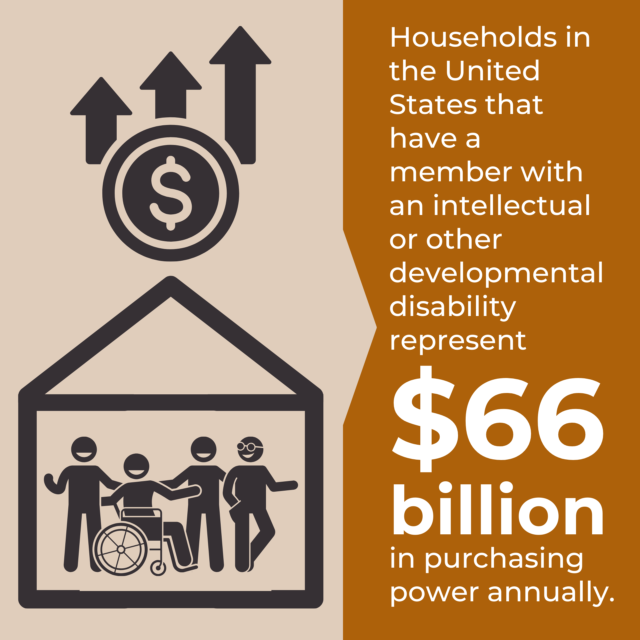

When it comes to dollars and cents, households in the United States that have a member with an intellectual or other developmental disability represent $66 billion in purchasing power annually, Crandell pointed out.

“So when I talk to businesses and industry, I don’t talk about, ‘hey, you should do this to be a good community member,’ I talk about $66 billion in purchasing power. I talk about tons of talent that’s not being used. That they can benefit from diversifying their workforce. And so the economic reasons to do it are what resonate with people.”