When Joshua Williams walked the graduation stage with his peers in 2014, he received a standing ovation. He didn’t know what the big deal was, his mother Mitzi Proffitt recalls. After returning for another year to complete a math credit and fighting to receive a diploma over a certificate, Joshua officially graduated from high school in 2015.

Williams, who turned 25 in April, celebrated at home when he graduated from Georgia Southern University in Statesboro this May. The moment was powerful for his family regardless. Amid the disruptions of the global COVID-19 pandemic, he has set up an internship with Georgia Southern’s inclusive post-secondary education (IPSE) program, EAGLE Academy, in the fall.

“One day, he said, ‘I’m finally proud of myself,’” said Profftt, who is also the former chair of the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD). “That is huge. He finally realized that he has worth.”

Williams underwent multiple rounds of interviews, and he didn’t want to tell anyone until it was a sure thing. His internship is set to begin the second week of August, and there are no current plans to postpone it due to COVID-19. The job is a first step towards competitive, integrated employment.

Individual administrators and teachers are given wide latitude to implement policy. The result is a jumble of stories and experiences that reflect a complicated process. Every day, families have tough conversations about aspirations and limitations. Invariably, the best results require hard, thoughtful work.

Individual administrators and teachers are given wide latitude to implement policy. The result is a jumble of stories and experiences that reflect a complicated process. Every day, families have tough conversations about aspirations and limitations. Invariably, the best results require hard, thoughtful work.

Transition Plans and IEPs

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandates that schools must incorporate transition planning into a student’s individualized education plan (IEP) by the time they turn 16. A transition plan is not a separate document; it is one component of a student’s overall IEP.

Elise James is a program specialist for transition outcomes at the Georgia Department of Education (GaDOE) with over 40 years of experience in special education. She explains that, according to IDEA, students’ post-secondary goals must be guided by their own interests, preferences and gifts.

“It’s really not our place to necessarily say, ‘You can’t do that,’” said James. “Our place is to provide [students] with the opportunities to see what is available and to experience it, so that they can make decisions based on their strengths.”

Districts can encourage families to begin planning earlier, but they are not required to do so. The Georgia Vocational Rehabilitation Agency (GVRA) services, specifcally called Pre-Employment Transition Services, become available when a student turns 14 years old. The GaDOE does not monitor transition planning below age 14.

“Now, in terms of the actual paper itself, there is no set IEP nationally or even statewide,” James said. “Every district can design their IEP in whichever way they’d like.”

In Georgia, district administrators are responsible for presenting options to parents, and resources vary by location. School administrators and professionals have a meaningful impact on student outcomes. In addition to assisting with transition, teachers in special education conduct lessons, collect data and facilitate IEPs for every student on their list.

When students with developmental disabilities leave high school, they have a variety of options. Post-secondary plans can include internships, apprenticeships, tech school, college, IPSE programs, employment, Project SEARCH, or other pathways funded via GVRA, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities or private pay. Each student is different, so there is no one best path. As families and students plan for new circumstances, it can be especially diffcult to manage their options, supports and the law.

When students with developmental disabilities leave high school, they have a variety of options. Post-secondary plans can include internships, apprenticeships, tech school, college, IPSE programs, employment, Project SEARCH, or other pathways funded via GVRA, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities or private pay. Each student is different, so there is no one best path. As families and students plan for new circumstances, it can be especially diffcult to manage their options, supports and the law.

Students’ Rights During and After Transition

The key difference between a student’s rights in high school and beyond is the responsibility of disclosure.

When students leave high school or turn 22 years old, the U.S. Department of Education’s Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) no longer applies to them.

Additionally, the Free and Appropriate Education (FAPE) rule is also gone after high school, making it harder to ensure accommodations are met. Under FAPE, schools cannot discriminate. Without that protection in college, the burden is on the student to request and prove need for accommodations.

But their rights essentially remain intact. Through adulthood, people with disabilities are protected by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). If a student chooses to go to college and passes the admission requirements, they have the right to receive accommodations under federal law, but they must self-disclose their disability.

In the public school system, it is the school’s job to identify and support students with disabilities. In college, a student must seek out and notify the university’s offce of disability services. To receive certain workplace protections, people must also disclose their disability to employers.

Profftt, the director of support services at Parent to Parent of Georgia (P2P), says that transition is when all the disability entities begin to really weigh on a parent. For instance, it took her seven years to get a Medicaid waiver.

“You’ve got to be ahead of it,” she said. “It’s hard, but you’ve got to have a plan. The IEP teams have to have a plan. The parents have to have a plan. There have to be some options.”

The choice to pursue higher education is made on an individual basis, and transition plans are meant to be as personalized as the supports named in a student’s IEP. Most schools use career assessments to help determine a student’s goals. Then, schoollevel professionals are meant to be a main source of guidance and exposure to potential opportunities.

“That over-arching goal should really be based on data,” said Angel Snider, a transition specialist and district success coach with Marietta City Schools. “It should be based on some kind of interview with the student, or an assessment.”

Navigating the Path

Despite federal and state guidelines, the process doesn’t always work as intended, and it has the potential to be a negative experience for both students and parents. Stacey Ramirez’s son Ryan loves travel and calendars. Given a date, he can spout its exact day of the week in under a minute. Before the coronavirus, he was visiting every state in the country – alphabetically. His canceled trip to Idaho would have brought him one closer to finishing the “I” states.

“For Ryan, it’s travel, and it’s books; it’s being with people; its movies, and it’s animals,” Ramirez said.

When Ryan was in high school, his gifts weren’t factored into his IEP. Ryan is a person with autism, and Stacey recalls his time in school as a nightmare fraught with relocations and court battles. Ryan attended Harrison, Kennesaw Mountain and Hillgrove High School in Cobb County. After a series of traumatic experiences, he left school with a Georgia Alternate Assessment (GAA) certificate when he was 18 years old.

“One day, he came home sweaty and upset,” Stacey said. As a part of the school’s vocational program, he had been in the yard picking up trash on a hot day. In another instance, a parent called Stacey asking about Ryan’s new job as a janitor at the school. At 16, he was not employed or compensated in any way; he was providing free labor, though not by choice. Stacey says the issue wasn’t the status of the work, but the lack of consideration for who her son is as an individual and lack of relevance to his transition plan.

When he left high school, Ryan wanted nothing to do with an IPSE program. He’s about to turn 26, and Stacey, who is the state director of the Arc Georgia, says the family is working to reconcile the post-traumatic stress of his high school experience to this day.

Until recently, Ryan worked at Zaxby’s. He liked the job, but he turned in his two weeks notice after they cut his hours. Stacey says life is more mundane in the pandemic. Still, she doesn’t miss the days of transition planning.

“The transition process is about the person,” said Stacey. “It’s about the student. It is not about what the school offers. The focus and spotlight have to continue to be on the student with a view of great capacity and community involvement. That’s not what’s being done now.”

Each family has its own experience. Not all are negative, but every story represents a winding path with its own anxieties. Ganesh Nayak recently wrote an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution about his son Ishan and life during the pandemic. Ishan, an 18-year-old with cerebral palsy, is a student at Pope High School in Cobb County. He’ll be in school until he’s 22, but the doors closed over two months ago due to COVID-19.

Each family has its own experience. Not all are negative, but every story represents a winding path with its own anxieties. Ganesh Nayak recently wrote an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution about his son Ishan and life during the pandemic. Ishan, an 18-year-old with cerebral palsy, is a student at Pope High School in Cobb County. He’ll be in school until he’s 22, but the doors closed over two months ago due to COVID-19.

Since Ishan was 16, he has had a transition plan. It’s updated every year with his IEP after the family completes a lengthy questionnaire, and the school passes along transition-related information.

“They’re doing their bit, and it’s up to us to see how to consume that information,” said Ganesh, who is the co-chair of the State Advisory Panel for Special Education in Georgia. Views expressed are his own as a parent. “We know the teacher very well because she lives in the neighborhood. That makes a big difference, actually.”

Ishan is a people person, and Ganesh says the primary focus of his schooling at the moment is more functional skills. The family still has time to figure out the specifics of Ishan’s plan, and they feel supported by his school. The Nayaks have looked into day habilitation programs, but there are no obvious fits in their area.

“Fortunately, we’ve had good teachers all along,” said Ganesh. “It makes a whole difference … That relationship should always be one of trust and collaboration rather than being at odds.”

“Fortunately, we’ve had good teachers all along,” said Ganesh. “It makes a whole difference … That relationship should always be one of trust and collaboration rather than being at odds.”

For now, the family deals with more immediate anxieties: the stream of breaking news, the risk of the virus and concern for their extended family in India. With the encouragement and assistance of his teachers, Ganesh says the stress of transition hasn’t yet come to the fore.

Despite the Nayaks’ positive experience with Ishan’s school, professionals can disappoint their students. When educators fail to center the child’s strengths and ambitions in transition planning, to consider them fully, they do more harm than good.

Stacey reflects on her experience for Ryan. “When I’m in the moment, of course it was hurtful and harmful … for my child to be considered less than he is, but upon reflection, it’s just a lack of the ability to see more,” she said. “In my heart of hearts, I think they thought they were doing a good job, and they were doing the right thing for Ryan. How dare you not be realistic about your son’s outcomes? You know?”

Ultimately, all students are guaranteed the same protections under the law, but the reality of every family is different. At Marietta High School, Snider uses her own education philosophy based on inclusion and collaboration – rooted in her high school experience witnessing segregated basement classrooms for students with disabilities.

“Everybody has goals that they want to obtain whether they have a disability or not,” Snider said.

“Everybody wants to have friends. Everybody wants to be successful. And success looks different for everybody. I think in order for us to function at our best, we need to include everyone in that plan. That just makes us better people.”

Better Outcomes

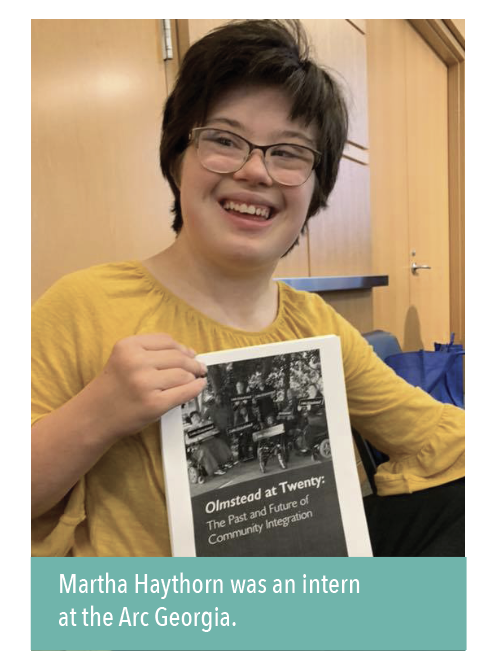

In the fall, Martha Haythorn will be among thousands of other incoming first years attending the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. The circumstances are less than ideal, but classes are expected to resume as scheduled. This spring, she graduated from Decatur High School. Haythorn received immense support from her family, teachers and mentors, but the accomplishment is her own. She is bubbly and confident, and she couldn’t be more excited for the future.

In the fall, Martha Haythorn will be among thousands of other incoming first years attending the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. The circumstances are less than ideal, but classes are expected to resume as scheduled. This spring, she graduated from Decatur High School. Haythorn received immense support from her family, teachers and mentors, but the accomplishment is her own. She is bubbly and confident, and she couldn’t be more excited for the future.

“They accepted me on the spot right after my interview,” Haythorn said. “There was a second of silence, and then there were tears coming down my face, real tears. I was so proud of everything that I’d worked for … They really saw that I am capable of being a college student. Yes, I have Down syndrome, but I’m more than that.”

Haythorn successfully underwent the application process for Georgia Tech’s IPSE program, Excel. She loves to learn and is honored to be able to learn new, interesting material among her peers. Haythorn plans to study psychology and U.S. history.

Her dream is to work as an advocate or lobbyist in Washington, D.C. to effect national change. She says all young people with disabilities should receive the same treatment and opportunities as their peers.

“It’s going to be a process,” said Haythorn. “There are certain steps you have to follow, but you will get there. It’s going to take time, but guess what? You’re going to be able to do it. You just need more time, and you will accomplish your dreams.”

Over the last year, she has worked three separate internships. Haythorn currently takes the MARTA blue line to her job as the policy intern for the Arc Georgia, where she’s found a mentor in Stacey. that with the help of parents, teachers or mentors, young people can find their true selves.

Over the last year, she has worked three separate internships. Haythorn currently takes the MARTA blue line to her job as the policy intern for the Arc Georgia, where she’s found a mentor in Stacey. that with the help of parents, teachers or mentors, young people can find their true selves.

“I always feel like a real intern, doing something that is totally me,” Haythorn said about her work with Stacey and the Arc. “I love it because [Stacey] really sees my ability. that it doesn’t matter if you have a disability. What matters is you have many abilities to do whatever you dream of, and whatever you dream can come true.”

“Talk about tapping into someone’s gifts and capacities,” Stacey said. “It’s hard to fnd a place where Martha’s not going to bloom.”

In the midst of the pandemic, Snider has warm stories from Marietta High School. As a transition specialist, she manages transition plans while working with students and referring them to agencies or programs. Through the school’s Check and Connect program, one mentor brought a student a birthday cake. Another student dropped out, only to re-engage with her mentor just recently.

“One of our students is doing work-based learning through the school, and he just started out doing an internship at an assisted living facility frst semester,” Snider said. “He has a low-incidence disability: wonderful young man, hard worker, very dedicated. They hired him right before the pandemic hit. He’s actually been working in [the] assisted living facility this whole entire time.”

“One of our students is doing work-based learning through the school, and he just started out doing an internship at an assisted living facility frst semester,” Snider said. “He has a low-incidence disability: wonderful young man, hard worker, very dedicated. They hired him right before the pandemic hit. He’s actually been working in [the] assisted living facility this whole entire time.”

The student is comfortable with the circumstances, as is his family, and the facility takes precautions. When the student frst got hired, Snider accompanied him to his training and helped out. Snider says she works hard to stay connected to local agencies and partners, including the parent mentor in her county, Susan Hand.

For parents who may be planning their own student’s transition at this moment, COVID-19 is a complicating factor. James notes that schools and the state are accountable to federal law, and the law remains the same.

“The requirements of transitioning students with disabilities did not get waived with the pandemic,” said James. “We’re still obligated to provide those services.”

After a delay due to COVID-19, the Marietta City Schools district is planning to start Project SEARCH in the fall of 2021. Since the coronavirus, Snider says she’s seen innovation and adaptability from professionals and advocates, as well as a willingness to share available resources virtually.

Vocational Rehabilitation, Other Resources and Paths to Employment

In March, Stacey applied for a case for Ryan through the Georgia Vocational Rehabilitation Agency (GVRA). There is no age limit for GVRA services, but people with disabilities who want support in going or returning to work must submit an application to receive assistance. Once the agency determines eligibility, they assign a case worker and begin developing an individualized plan for employment, or work plan. They’ve been in contact, but Stacey says it may not be the time for Ryan to get a new job.

Lee Brinkley Bryan is the transition services director at GVRA; she oversees hundreds of staff around the state. Bryan says services will continue through the pandemic, and she notes that anyone experiencing communication delays should call the customer care number on their website.

Lee Brinkley Bryan is the transition services director at GVRA; she oversees hundreds of staff around the state. Bryan says services will continue through the pandemic, and she notes that anyone experiencing communication delays should call the customer care number on their website.

“The offices, like all other state offices, are closed, and people are teleworking. But our work continues,” said Bryan. “We are in uncharted territory with COVID-19 just like everybody else. We’re doing everything we can to continue to provide services.”

In the past, GVRA has been criticized by parents and advocates for a variety of reasons, from poor service to understaffing. Proffitt prefers to recommend other agencies to parents before GVRA. Bryan said that in some cases, clients are reassigned to new counselors, and she asks for feedback from any family with concerns.

“[GVRA] has faced some challenges over the last few years with our staffing and our ability to cover the schools as we would like to,” said Bryan. “But plans are in the works for increased staffing across the state … I don’t want [parents] to read these words and think we’re describing a world they don’t recognize. I want there to be hope.”

There are other paths to employment beyond GVRA; everyone has their own potential. It might take a search, though. There are many resources online, and parents can get support from local groups or agencies. Profftt even suggests making the case directly to a business, taking direct initiative to secure the dream of gainful employment.

“My biggest thing is, nobody wants to go into companies and try to sell it to them,” says Profftt, Joshua’s mom mentioned earlier. “Because all we ever hear is, ‘Oh, your child’s a liability. Oh, we don’t want them to lose their services.’”

Transition councils are another resource for families of young people with developmental disabilities. Profftt has sat on the Three Rivers Transition Council for the last few years. Councils are made up of teachers, parent mentors, advocates and agency representatives that collaborate to bring tools and resources to families. Council presence depends on location, but location and contact information can be found on the P2P website.

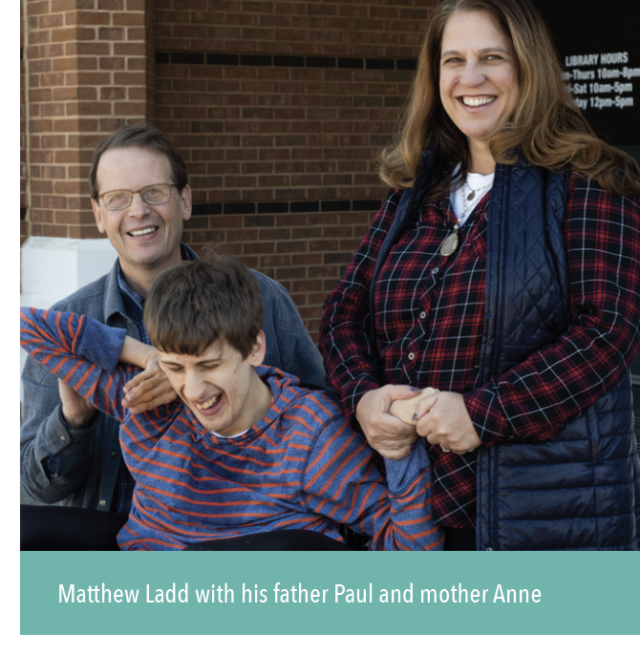

Anne Ladd, a family engagement specialist at the GaDOE, says most parent mentors in the Georgia Parent Mentor Partnership (PMP) work on transition as well as K–12 education supports. Ladd says parent mentors bring different skill sets and dynamics to each district they serve.

Anne Ladd, a family engagement specialist at the GaDOE, says most parent mentors in the Georgia Parent Mentor Partnership (PMP) work on transition as well as K–12 education supports. Ladd says parent mentors bring different skill sets and dynamics to each district they serve.

“Parent mentors are also those go-to experts on family, school and community connections in their school district or in their department,” said Ladd. “They’re the boots on the ground. It’s a path they’re going to have to go down.”

Ladd’s son Matthew graduated high school in 2017. Like many other parents’ stories, things didn’t go according to plan. Despite uncertainty, Ladd notes that they were able to pivot by connecting to community resources and developing strong relationships.

“Things did not go as we expected that they would,” said Ladd. “You love to have everything laid out, and then, wham! It’s not going be that way. What was really important for us was the relationships and the connections that we had established.”

So, When Do Parents Start?

Many professionals and parents who have gone through the process recommend parents begin planning as early as possible. Exposure, encouragement and inclusion are essential building blocks of any transition plan. Seeds of possibility can be planted by educators and parents at a young age. Across the state, families are in different stages of the process.

“It’s a tough conversation,” said Nayak. “There’s always the anxiety about the future. Because we are an immigrant family, we don’t have any immediate family here, and that makes it that much more difficult when you think about what’s next. What’s after we go? Those are diffcult questions, and we’re still grappling with that.”

Education protections and supports are constantly changing. James says even though federal law mandates transition planning by age 16, parents can’t start the conversation too early.

“The truth of the matter is that students are only going to know what they have been exposed to,” said James. “You really have to start the day you put the pen to the paper to write the first IEP.”

Planning for transition is a natural extension of the IEP process, and both can involve the same frictions. Dedicated professionals and devoted parents agree that collaboration and consideration of the individual are essential. Snider has children of her own. She recognizes her teachers know her daughter as a student, but that isn’t everything.

“I know her in a different way,” Snider said. her go to sleep at night, and what she likes in the morning when she wakes up. it needs to be a team approach. I think the earlier a parent gets started looking at things and talking about the future, the better.”

“I know what helps Things like that … This feature is Part 2 of GCDD’s Education Series to help families and students navigate the IEP process in order to transition from high school into college or employment. Part 1 covered education rights and the IEP process from primary years through high school and can be accessed on the GCDD website.

This feature is Part 2 of GCDD’s Education Series to help families and students navigate the IEP process in order to transition from high school into college or employment. Part 1 covered education rights and the IEP process from primary years through high school and can be accessed on the GCDD website.