From the initial fact-finding process to the end result, leaders in the disability community are giving a big thumbs-down to the new Georgia voting booths as election season is here. While the Georgia primary election has been rescheduled to June 9 due to the COVID-19 outbreak; and the Secretary of State (SOS) will be mailing absentee ballots to all registered voters for the primary; the accessibility of the new machines will be an important factor in the general elections.

Not having the best, most accessible machines creates problems. “There could be an effect on the actual vote count if votes are unconfirmed, or worse, inaccurate,” says Cheri Mitchell, an advocate for the Georgia Advocacy Office. “Aside from the impact on votes, however, voters with disabilities may start staying home instead of voting.”

Not only will their votes be marginalized or excluded, Georgia could slip further behind in terms of accessibility, threatening the participation of voters with disabilities in the future. “There is no single definition of voter suppression, per se, but we can extrapolate the meaning of the term by looking at examples such as voter roll purges, ID requirements, restricting access to absentee voting and voter registration restrictions,” adds Mitchell.

Not only will their votes be marginalized or excluded, Georgia could slip further behind in terms of accessibility, threatening the participation of voters with disabilities in the future. “There is no single definition of voter suppression, per se, but we can extrapolate the meaning of the term by looking at examples such as voter roll purges, ID requirements, restricting access to absentee voting and voter registration restrictions,” adds Mitchell.

All of these examples have the effect of making voting more difficult and Georgia’s new voting machines will certainly do that for some. It may be unclear what the intention was in selecting the specific machines or not including certain accessibility features that would make the machines useable by all voters. Regardless, the impact is the same: the new machines will make it more difficult for people with disabilities to vote in Georgia.

The voting machines of yesteryear were challenging. “There had to be a better way,” said Robert Smith, president of the Decatur chapter of the National Federation for the Blind (NFB).

“The SOS’ office has a legitimate interest in making sure that the voting machines are secure, and protecting that interest means that Georgia is using these new machines. However, disability rights are no less important than voting security, and we have to be careful to avoid assuming that we can’t have both. We can and we must,” says Mitchell.

Voters with motor impairments or significant vision impairments are unlikely to be able to use the new voting machines independently. Then-SOS Cathy Cox agreed and ordered new machines that were more sensitive to the needs of people with disabilities. “When Cathy Cox was in office, the blind said that we wanted to have a say, and we did,” said Smith.

Still there were issues, mostly over validation and technology. Governor Brian Kemp wanted new machines. “The office has made a big effort to try to make the voting as accessible as possible to people with any disability and have the voting be the same as everyone else,” says Walter Jones, communications manager for the SOS. “We went through a whole process and even had roundtable discussions with various disability organizations.”

At that meeting were senior members of current SOS Brad Raffensperger’s staff, including State Elections Director Chris Harvey, who said his mother also was a person with disabilities. “This is personal for me that we get out and serve people with differing abilities,” he said. One of the sticking points is that Raffensperger brought them much later into the decision-making than Cox.

“We recommended the machines that Maryland uses, and they didn’t choose those,” says Dorothy Griffin, president of the NFB in Georgia. “It’s not an improvement. I liked the older machines better.” Instructions on using the new machines are “very clear,” but Jimmy Peterson, executive director of the Georgia Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, added that he wished, “all the amendments were in the [American Sign Language] version instead of the English version.” The new machines are almost the same as the old, except to print the ballot to vote. So, what’s the problem? A big negative is check-in privacy. Poll workers can scan identification cards, but not a person’s party affiliation, so it must be given to the worker. “That’s not privacy,” says Griffin.

Technology is another issue. “Using the headset is a bit confusing, and it repeats the instructions over and over again. It drives you a little batty,” says Griffin Many, especially seniors, may not be comfortable with technology. Those with poor hand coordination could also be impacted, she adds.

Smith also questions whether poll workers might not be properly trained. “Is there enough training so the poll workers will know what to do right away if a person who is blind or visually impaired comes in?” Jones says there is training as well as a video helping poll workers respect and aid people with disabilities.

There also are issues with validation With the new system, a person will be given a paper copy of their ballot to ensure that it is correct and submitted.

Of course, for anyone who can’t see, being given a piece of paper to read is a wasted effort. Bringing smartphones, other artificial intelligence devices or magnifying glasses are a “Band- Aid,” says Gaylon Tootle, an independent living advocate and vice president of the NFB in Augusta.

Both Griffin and mith want a scanner that, when you insert the ballot, will verbally read the vote so the person can approve. Smith says the state claims scanners are too expensive. “If I can’t read my ballot, a scanner is the next best thing. It puts us on equal footing. I want a paper trail as well as it being electronically recorded.”

By law, no one is allowed to bring smartphones with them into the voting booth. However, the voter election board held hearings to change that regulation.

In response, the SOS’ office will now allow voters with disabilities to verify their printed ballots before casting them. The system allows voters to make their choices on a touchscreen device and then print their ballot for review before casting.

According to a press release from the SOS’ website, “the new system has the ability to adapt to various accessibility needs, from larger type fonts and altered contrast to audio instructions and sip-and-puff manipulation.”

It is every citizen’s right to vote. “The people who are elected make decisions about equality, programs and services. We need equality, programs and services for all! That means ALL need to vote,” said Mitchell. “Not only is it every person’s right to vote, every person has the right to vote privately in Georgia. If you are a person with a disability, your ability to read, mark or submit your ballot independently may be impacted. Accommodations like assistive technology (AT) devices are the only way that you can vote in private, just like everyone else.

Smith acknowledges the cost, “but we pay taxes.” Adding, “We’re going to keep pursuing it until it gets changed. We’re encouraging all people, especially in the blind community, to get out to vote.”

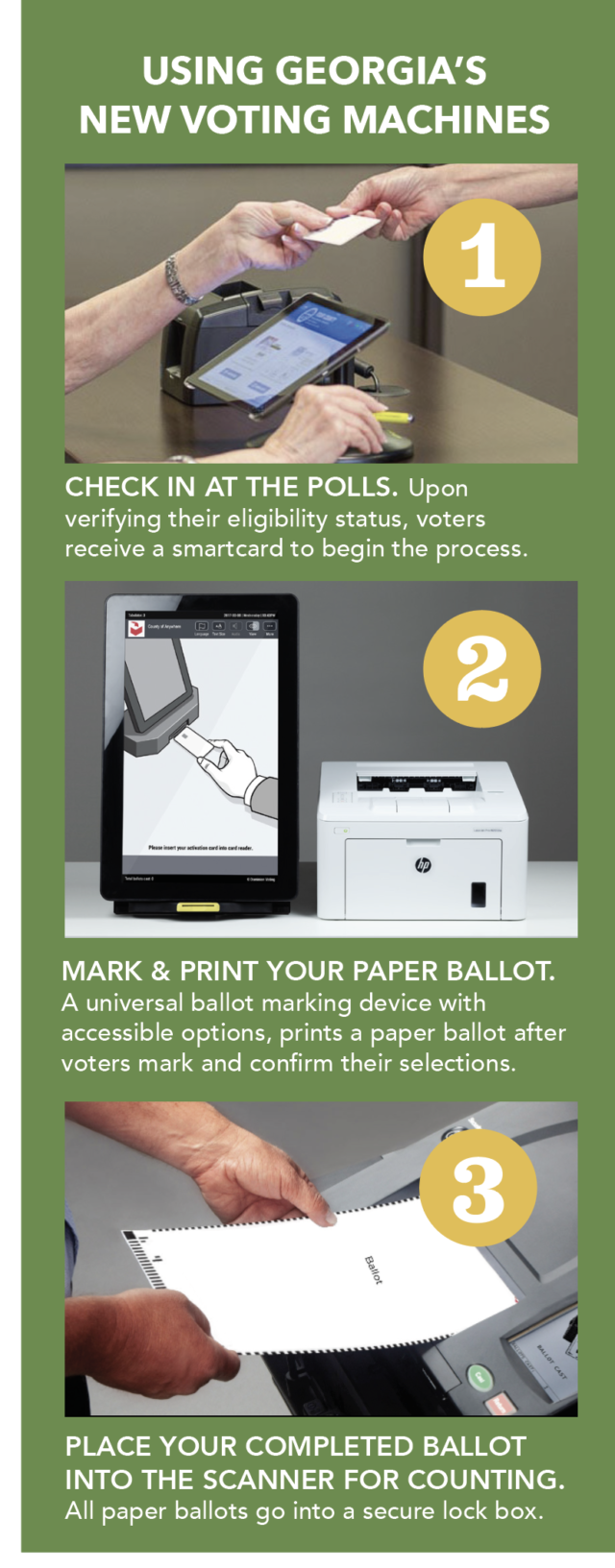

USING GEORGIA’S NEW VOTING MACHINES

USING GEORGIA’S NEW VOTING MACHINES

- CHECK IN AT THE POLLS. Upon verifying their eligibility status, voters receive a smartcard to begin the process.

- MARK & PRINT YOUR PAPER BALLOT.A universal ballot marking device with accessible options, prints a paper ballot after voters mark and confirm their selections.

- PLACE YOUR COMPLETED PAPER BALLOT INTO THE SCANNER FOR COUNTING. All paper ballots go into a secure lock box.

VOTING PROBLEMS?

I a person with disability had trouble voting or was not treated properly, they can contact the Georgia Advocacy Office (GAO), which receives federal funding under the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) to advocate to ensure that people with disabilities have access to the voting process.